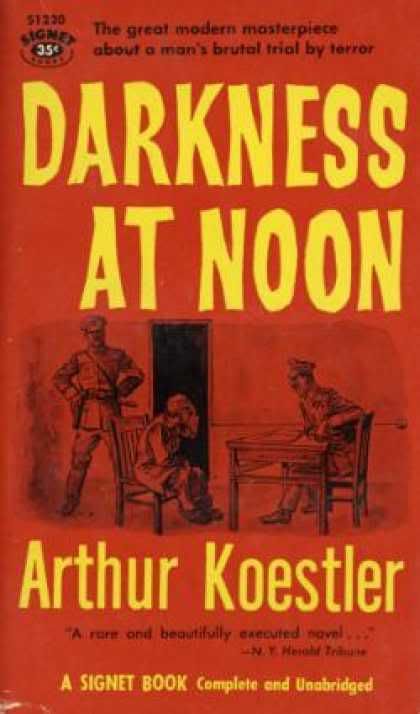

This splendid novel is set in the tumultuous Soviet Union of the 1930s during the treason trials. Rubashov, the protagonist and a hero of the revolution, is arrested and jailed for things he has not done, though there is much about the current Soviet state that veered from his ideals as a revolutionary. His investigators, Ivanov and Gletkin, seek a public confession and interrogate him using a number of methods. Through the ordeal, Rubashov reaches an epiphany or two while his interrogators suffer the cruel fate of the Soviet machine. Darkness at Noon succeeds as political/historical novel, but even more so as a refreshing tale of the human spirit.

Original title: Sonnenfinsternis

Author: Arthur Koestler

Genre: Novel

Publisher: Scribner

Media type: Paperback, Audio Book

Pages: 288 pp

ISBN-13: 978-1416540267

Publication date: 1940

Reader Review

Penalty is Death - Guilty of Political Divergencies

I first read Koestler's Darkness at Noon in high school, close to 30 years ago. Although I cannot recall my earlier reaction to the book, I am certain that I was not prepared, as a 17-year old, to appreciate either the literary beeauty or socio-political importance of Koestler's masterpiece.

I came back to this book for two reasons. I had just finished reading Volkogonov's "Stalin" and "Trotsky" and Solzhenitzyn's Red Wheel (Volume I). Darknesss at Noon seemed to be the next appropriate book to pick up off the shelf.

I had also been reading about the remarks President Clinton made (alluded to by other reviewers) to Sid Blumenthal indicating that he felt "like the prisoner in Darkness at Noon."

It is, perhaps, either a sad testament to human nature, or an indicia of the power of great literature, that the story of the fate of one (fictional) man, Rubashov, can feel more compelling than the narrative description (in "Stalin" and "Trotsky") of the fate of millions.

Further, whereas Volkogonov's works go a long way towards explaining what happened and how it happened, Rubashov's self-crticial analysis, and his dialogues with Ivanov and then Gletkin go a long way towards explaining why the purges happened. It helps explain the mindset of those many, like Rubashov, who confessed their non-existent sins before their ineveitable demise. It also goes a long way to explaing why so many millions of people actively participated in the denunciations that accompanied the purges and show trials.

Clinton's comparison to Rubashov is rich with unintended irony. Perhaps Clinton, like me, had not read the book since high school, and felt that Rubashov was the purely innocent victim of a prosecutorial system run amok. However, Koestler makes it clear that Rubashov was not merely a vicitim of Stalin, or Stalin's henchmen, but of the system that Rubashov (a hero of the revolution) himself played an important role in creating. Rubashov spent a life filled with deceit, manipulation, and even murder, on behalf of his party and its "core values". The doctrine of the end justifying the means was a cornersone of Rubashov's philosphy and morality. Whatever "core values" existed at the beginning of his revolutionary life with the party had long since withered to nothingness by the time of his imprisonment. Consequently, if President Clinton's comparison of himself to Rubashov was based upon the idea that Rubashov was a purely innocent victim, he is just wrong. To the extent Clinton was aware that Rubashov was in no small way responsible for creating the milieu under which this despicable actvity takes place - then he is more self-aware than I had previously given him credit for.

Finally, the book is just darn well-written. Of particular beauty and impact are Rubashov's dialues with his interrogators.

Pick up this book and read it.

- by Michael Wischmeyer

A classic

"The characters in this book are fictitious. The historical circumstances which determined their actions are real. The life of the man N. S. Rubashov is a synthesis of the lives of a number of men who were victims of the so-called Moscu Trials".That is part of the dedicatory that Koestler wrote for his book, "Darkness at noon".

Arthur Koestler (1905-1983) was a person that believed in the progress that Communism was supposed to bring, but that became disillusioned in the way in which that dream was being carried out in the URSS. He wrote many books that give expression to his feelings of disenchantment, but "Darkness at noon" is probably the most popular one.

Not overly long, and very easy to read, this book is the story of Rubashov, an old communist who took part in the revolution and who is very loyal to the "Cause". Strangely enough, he is accused of treason, and taken to jail, where he must face harsh interrogatories. While he is in jail, Rubashov experiences flashbacks that allow us to know more about him, and the things he did due to his devotion to the Party. He betrayed people he loved, and those he appreciated, for no other reason than obedience to the Party and fear of going to jail.

We can have an idea of Rubashov's feelings and ideas all throughout his ordeal thanks to the fact that "Darkness at noon" is written in the first person. After a while, we are Rubashov, and like him we are surprised, outraged, desperate and ultimately resigned to our luck.

In the beginning, Rubashov says that he isn't a traitor and that he hasn't done the things he is accused of. But slowly our main character starts to come to terms with the idea that the truth of the accusation isn't really important, what matters is to serve the country. And if the leader (Number one) says he is to be blamed, he must have done something....

The prisioner writes a diary, where he dwells upon the nature of men, and politics. He thinks that after the revolution he defended so passionately, an individual is defined merely as "a multitude of one million divided by one million". The individual doesn't matter because only the "Cause" matters. Regarding politics, he concludes that at the end only one thing is clear: "the end justifies the means". Is it any surprise, then, that the tone that pervades this book is so gloomy?.

On the whole, I highly recommend "Darkness at noon" to all of you, for two reasons. To start with, it is a literary masterpiece, beautifully written and accessible to the average reader. Secondly, and more important, it also shows us once again that every attempt to forget that the end doesn't justifies the means ends in a nightmare.

- by M. B. Alcat "Curiosity killed the cat, but satisfaction brought him back"

Psychological Examination of Stalinist Show Trials

Set during the Stalinist purges and show trials, `Darkness at Noon' presents a fictionalized account of the interrogation and breaking of a (former) communist leader `Rubashov'. Under Stalin, 'former communists' were limited to those persons about to be executed, already executed, or waiting to be uncovered. As an original Bolshevik, a leader of the 1917 revolution, Rubashov's disillusionment was simply inadmissible to Number One (as Stalin is referred to by Koestler).

Koestler explores the journey of Rubashov from the knock at the door through the final denouement. The reader observes Rubashov, who plays the role of narrator, as he undergoes the psychological change from a determination to resist to nearly total capitulation. Rubashov manages to hold to some crumbs of self-respect, but yields to the logic of the revolution as more important than any individual even when the accusations are complete fabrications.

`Darkness at Noon' is precisely imagined with its details of Rubashov pacing the floor of his small isolation cell, the coded tapping between adjacent cells, and the deprivation of physical comforts that make the subsequent small graces, such as limited outdoor exercise, become precious by comparison. This much of the tale was informed by Rubashov's experiences as a prisoner during the Spanish Civil War. Koestler's examination of the psychological destruction of the prisoner is fascinating, although at times it briefly lapses into stultifying disquisitions on the distorted Stalinist political philosophy.

Koestler himself was a German communist through much of the 1930's before immigrating to Britain, leaving the party and becoming an influential ex-communist. George Orwell's excellent essay about Koestler is readily available on the Internet (google `arthur koestler orwell').

Darkness at Noon was the middle book of an unusual trilogy of loosely related subjects: Gladiators and Arrival and Departure (20th Century Classics). Readers may also wish examine Victor's Serge's The Case of Comrade Tulayev (New York Review Books Classics).

Highly recommended for anyone interested in the era of communism in its Stalinist form or more broadly in the perverse ability of humans to place greater meaning in abstract and abstruse ideology than in the actual lives of other humans.

- by Douglas S. Wood "Vicarious Life"

What do you think of this book? Please share your thought with us!

No comments:

Post a Comment